Key Takeaways

- Understand unit economics so every product and order is judged by contribution margin, not vibes, helping you see which SKUs actually make money after all variable costs.

- Use a simple contribution margin formula and break-even math to set clear sales targets and avoid scaling campaigns that lose money on each order.

- Adjust pricing, AOV strategy, and CAC targets through a unit lens so bundles, upsells, and channels are optimized for profit per order, not just top-line revenue.

- Review unit economics by channel, product line, and stage of growth so you can reallocate budget toward profitable bets and catch unprofitable patterns before cash runs out.

If you are running a small product brand, you probably know the feeling of “great sales, scary bank account.” Revenue looks fine, but cash is tight and you are not sure which products are actually pulling their weight.

Here is the mental shift I have seen across hundreds of Shopify brands I have worked with and interviewed on Ecommerce Fastlane: once founders understand unit economics, everything changes. Decisions stop being emotional and start being math. When you understand unit economics small brands can grow fast without quietly burning through cash.

What Unit Economics Actually Means For A Small Brand

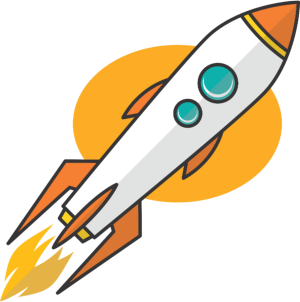

Visual flow of per unit revenue and costs into contribution margin. Image generated by AI.

Unit economics is simply this: on each sale, do you keep money after all direct costs, or do you lose money and hope volume saves you later?

For ecommerce, “one unit” can be a single product, an average order, or a subscription box. What matters is that you pick one definition and stay consistent.

For a small product brand, the core pieces are:

- Revenue per unit: selling price after discounts.

- Direct costs per unit: product cost, packaging, pick and pack, shipping, payment fees, and any per-order app fees.

- Marketing cost per unit: how much you spent to acquire that order (your CAC on a per-order basis).

- Contribution margin per unit: revenue minus all those variable costs.

If contribution margin is negative, every sale digs the hole deeper. If it is positive and healthy, you are at least getting paid to acquire customers and can work on repeat purchases and LTV.

If you want a more formal definition, the unit economics ecommerce glossary from Pen and Paper is a solid short read on how operators use this thinking in practice: Unit Economics: Ecommerce Data Glossary.

The Core Formula And Your Break Even Point

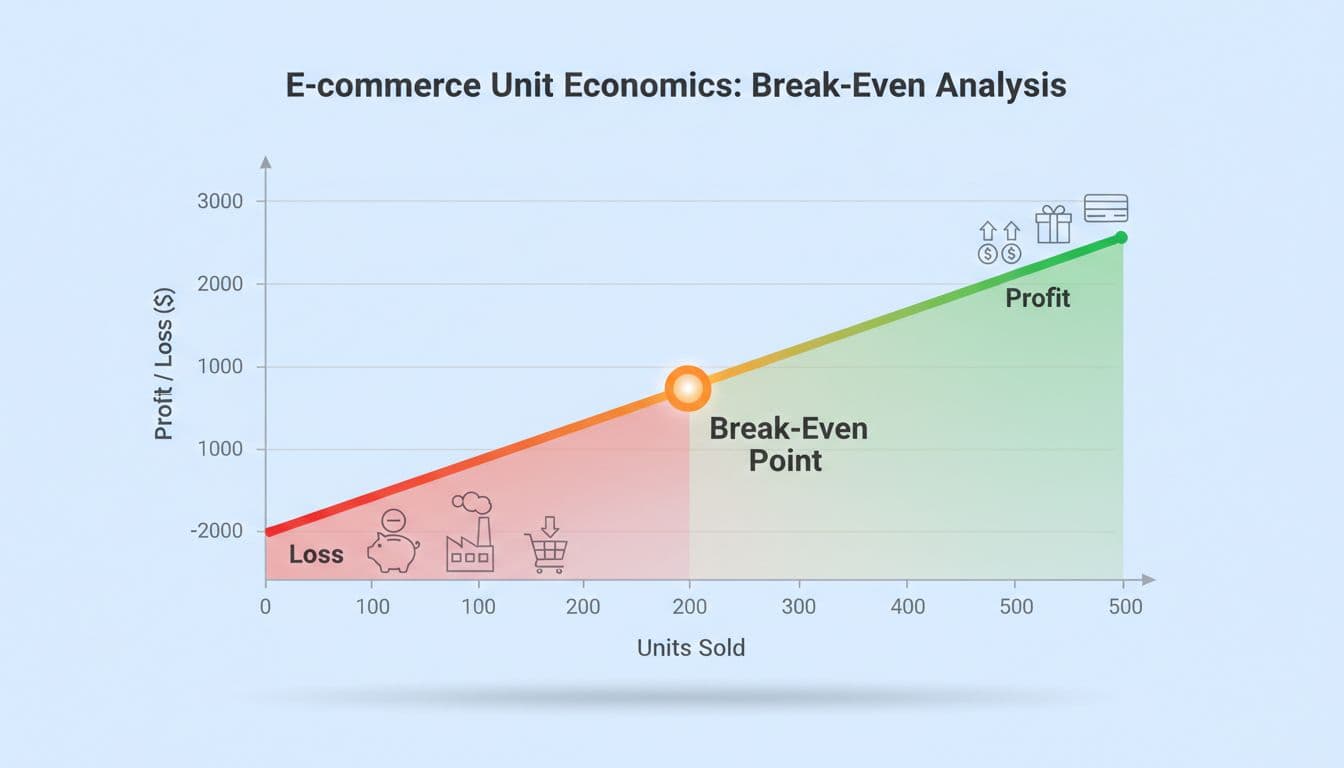

Simple break even view of profit and loss by units sold. Image created with AI.

Here is the simple version you can write on a sticky note:

Contribution margin per unit = selling price

minus product cost

minus shipping and fulfillment

minus payment and platform fees

minus marketing cost per order.

Once you know that number, you can figure out how many units you need to sell to cover your fixed costs like salaries, rent, and software. That is your break even point.

A quick example:

- Selling price: $60

- Product + packaging: $18

- Shipping + fulfillment: $9

- Fees (payment, platform): $3

- Marketing CAC per order: $15

Contribution margin per order = $60 − $18 − $9 − $3 − $15 = $15

If your monthly fixed costs are $30,000, you need:

- Break even orders = $30,000 ÷ $15 = 2,000 orders per month

Here is the pattern I keep seeing when we go deep on P&Ls with founders. Brands that maintain 50 to 70 percent gross margin on product and keep marketing spend under 30 percent of revenue per order usually reach operating profitability in 2 to 4 quarters once they get consistent traffic. Brands outside those bands either starve for cash or live on fundraising.

If you want a calculator to speed this up, Lucid has a useful walkthrough that matches how investors and CFOs think about it: Unit Economics Calculator: Step-by-Step Guide.

Pricing, AOV, And CAC Through A Unit Lens

Unit economics is not a finance side quest. It touches almost every decision you make on pricing, bundles, and paid traffic.

On pricing, most founders start with a rough “keystone” multiple and call it a day. That is how you end up with a best seller that drives revenue but almost no profit. At minimum, pricing has to respect both your product margins and the CAC you see on your main channels.

If you have not done this work before, start by revisiting your price points with a margin-focused guide like this one on optimizing product pricing for higher margins: The Price Is Right: 14 Strategies For Finding The Ideal ….

On the revenue side, your average order value (ATV or AOV) is a quiet hero. A $50 CAC is painful if your AOV is $55 and contribution margin is thin. The same $50 CAC can be amazing if your AOV is $140 and your gross margin is strong. This is why in so many Ecommerce Fastlane interviews, 7 and 8 figure founders talk about AOV lifts from bundles or post-purchase upsells as the thing that made their ad spend suddenly “work.”

Finally, CAC itself must be managed relative to contribution margin, not just ROAS dashboards. You can tolerate a higher CAC when:

- Your contribution margin per order is strong.

- Your retention engine (email, SMS, subscriptions) is dialed in.

- You have clear payback math, not hope.

If you want more advanced reading that connects unit economics directly to ecommerce campaigns, Magnet Monster has a good breakdown from the retention side: How to Calculate Unit Economics for Your eCommerce Brand.

Stage-By-Stage: How To Put Unit Economics To Work

The way you use unit economics depends on your stage, but the core logic is the same.

If you are just starting or under $50k a month, keep it simple:

- Pick 1 or 2 hero SKUs and calculate contribution margin per order.

- Track basic acquisition cost from your main channel.

- Stop any offer where you are clearly losing cash per order.

Pair this with a basic KPI view so you are not drowning in data. The “six pack” approach we use in Ecommerce Fastlane, built around a handful of metrics like traffic, conversion, orders, AOV, sales, and ROAS, is a great companion to unit economics. You can see that explained in more detail here: 6 Key ECommerce Metrics You Need To Guide Your ….

If you are in the mid six to low seven figure range, upgrade the model:

- Calculate unit economics by channel or campaign, not just blended.

- Separate first-order CAC from blended CAC so you can see payback.

- Tie contribution margin to SKU families, not just “store average.”

This is where many operators I have spoken with realized their “hero” product only looked good because returning customers were hiding weak first-order math.

If you are at multi seven or eight figures, treat this like an ongoing operating system, not a one-time audit:

- Review unit economics by channel, country, and product line monthly.

- Tie paid media budgets to clear contribution and payback rules.

- Involve finance, marketing, and ops so everyone is staring at the same math.

At this level, unit economics is how you decide which bets to double down on and which to kill, long before cash gets tight.

Common Pitfalls I See In Small Product Brands

A few patterns come up again and again when we talk unit economics with founders.

Ignoring shipping and fulfillment in margin math. Many brands only subtract COGS, forget pick and pack, packaging, and rising carrier costs, then wonder why profit is lower than their spreadsheet.

Blending all marketing into one CAC. Paid social, influencer, affiliate, and organic all mix into one number. That hides the channels that are quietly unprofitable. The fix is to calculate CAC and contribution margin by channel at least once a month.

Scaling before the unit works. Founders crank up ad spend because MER or on-platform ROAS looks nice, while contribution margin per order is negative. The classic warning from finance leaders applies here: do not scale something that loses money per unit. Toptal has a clear breakdown of why that logic kills companies: Don’t Scale an Unprofitable Business: Why Unit Economics (Still) Matter.

Confusing profit with cash. You can have positive unit economics and still run out of cash if you grow fast, buy inventory, and pay for ads long before revenue comes back. That is why I often pair this topic with a conversation about cash flow management tips for ecommerce: Cash Flow Management: Why Cash Flow Can Be Even More Important Than Profit | Ecommerce Fastlane.

A Simple Checklist You Can Run This Week

Here is a quick, practical pass you can do without hiring a CFO:

- Pick your top 3 products or bundles by revenue.

- For each, calculate selling price, COGS, shipping, fees, and average CAC per order.

- Compute contribution margin per order and rank them from best to worst.

- Compare that to how you feature products on-site and in ads.

- Shift budget and homepage real estate toward the most profitable units.

- Set a simple rule for yourself: “We never scale a campaign where contribution margin per order is negative.”

Run this every quarter and you will catch issues long before they show up as “mystery” losses.

Summary

Unit economics is the simple but powerful idea that every order either helps or hurts your brand, and you can measure that with contribution margin. By subtracting all variable costs—product, packaging, shipping, fees, and acquisition—from your selling price, you see how much is left to cover fixed costs and profit, which is exactly how investors and operators evaluate healthy ecommerce growth. When you anchor decisions in this math, “great sales, scary bank account” becomes a solvable problem instead of a mystery, because you know which products, offers, and channels are truly carrying their weight.

For founders, the most practical move is to start small and concrete. Pick your top 3 products or bundles and calculate contribution margin per order, then compare that to how hard you push them in ads, email, and on your homepage. If a “hero” SKU looks great on revenue but weak on margin after CAC, you either improve pricing, AOV (through bundles and upsells), or pause scaling until the unit works. As you grow, move from blended numbers to channel-level and campaign-level unit economics so you can see, for example, that Meta might be profitable while a certain influencer or marketplace partnership quietly burns cash.

The biggest risk isn’t slow growth; it is scaling something that loses money on each sale, a trap many venture-backed brands have fallen into when they chased MER or ROAS without checking contribution margin. To avoid that, set a simple rule: you do not scale any campaign where contribution margin per order is negative, and you review the numbers at least quarterly by product and channel. Over time, unit economics becomes your operating system, guiding budget allocation, pricing tests, and inventory bets so you can grow faster without relying on fundraising to cover avoidable losses.

If you want to go deeper, pair this guide with a unit economics calculator and a short list of core metrics—traffic, conversion, orders, AOV, sales, and ROAS—so you can tie the story together in one place. Your next step is simple: block an hour, run the math on one hero product and one main channel, and see whether each new order is truly adding fuel or quietly draining the tank. Once you have that clarity, you are already ahead of most brands in your space—and you can start making decisions with confidence instead of guesswork.

Frequently Asked Questions

What are unit economics for a small ecommerce brand, in simple terms?

Unit economics tells you how much profit you make (or lose) on each order after counting all variable costs like product, shipping, fees, and marketing. It answers the question, “Does each sale help my business, or am I hoping volume will fix bad math later?”

What is contribution margin, and why does it matter more than gross margin?

Contribution margin is your selling price minus all variable costs, including marketing CAC, not just product and shipping. It matters because it shows what each order actually contributes toward fixed costs and profit, which is the real foundation for sustainable growth.

How do I calculate contribution margin and break-even orders for my brand?

Start with a single order: subtract COGS, packaging, shipping, payment fees, platform fees, and average CAC from your selling price to get contribution margin per order. Then divide your monthly fixed costs (like salaries, rent, and software) by that contribution margin to find how many orders you need to break even.

How do unit economics affect my pricing strategy?

Pricing that ignores unit economics can create “bestsellers” that drive revenue but little or no profit. When you factor in CAC and all variable costs, you may need to raise prices, push higher-AOV bundles, or drop low-margin products that can’t support your acquisition costs.

Why is AOV so important when looking at CAC and unit economics?

A high CAC can still be healthy if your AOV and margin are strong, because each order contributes more dollars after costs. By lifting AOV with bundles, cross-sells, and post-purchase offers, you spread acquisition cost over more revenue and improve contribution margin per order.

Should I look at unit economics by channel or just for the whole store?

Looking only at blended numbers hides which channels are profitable and which are quietly draining cash. Reviewing contribution margin and CAC by channel or campaign helps you reallocate budget toward the sources with the healthiest per-order economics.

Why is it dangerous to scale a campaign if my unit economics are negative?

If you lose money on each order, scaling just means losing money faster, a pattern finance leaders repeatedly warn against. Many startups that “grew like crazy” but never fixed unit economics eventually stalled when capital markets stopped funding their losses.

Can I have good unit economics and still run into cash problems?

Yes, even with positive unit economics, fast growth, inventory buys, and ad spend can strain cash if money goes out long before it comes back. That is why unit economics should be paired with cash flow planning so you know not only if orders are profitable, but also whether you can afford the timing of those profits.

How should early-stage brands (under $50k/month) use unit economics without overcomplicating things?

Focus on 1–2 hero products, calculate contribution margin per order, and track basic CAC from your main acquisition channel. Stop scaling any offer where you are clearly losing money per order and revisit pricing or AOV tactics before pushing harder.

What simple routine can I use to keep unit economics front and center as I grow?

Once a quarter, pick your top products, calculate contribution margin per order and CAC by channel, and rank them from best to worst. Then shift budget and site placement toward the winners, cut or fix the losers, and keep a non-negotiable rule not to scale any campaign with negative unit economics.